When Dylan’s Skull Was Crushed in a Car Accident, Doctors Said Recovery Was Hopeless. They Were Wrong.

Updated: Jul. 29, 2016

The human mind has a previously hidden aptitude for recovery. Here is the story of one young man’s journey back from the brink.

Day Zero

Despite its encircling fortress of bone, the human brain is especially vulnerable to physical insult. There are approximately 1.7 million traumatic brain injuries in the United States every year, and although most are mild or moderate, thousands result in severe brain damage. Those injuries always happen on the same day: day zero, a day that marks the start of a fateful and often flawed prognostic calendar.

For 19-year-old Dylan Rizzo, day zero was December 28, 2010. Tall and slender, with a sly sense of humor, Dylan was a sports nut, playing hockey and competing in the high jump for his high school in Lynnfield, Massachusetts, and rooting for the Boston Bruins.

At 8:30 p.m., as Dylan was driving to play video games at his friend Ryan’s house, he called his mother. He couldn’t find his Xbox controller.

“You always move my stuff!” he said.

“No, I don’t,” Tracy Rizzo replied. After hanging up, she found the controller in her car. “I called Dylan,” she recalled. “He didn’t answer.” She texted Ryan:

“When Dylan gets there, just tell him I got the controller.”

A few moments later, Ryan called Tracy Rizzo back. He said there had been an accident.

Day 1

Emergency responders found the driver’s-side door of Dylan’s SUV crunched into a telephone pole. Dylan was unconscious. His breathing sounded like the gurgling of a straw in a near-empty cup. He had traveled barely 200 yards before striking the pole, possibly after hitting black ice. He wasn’t wearing a seat belt.

It took responders eight minutes to pull him out. There was so much blood and lacerated flesh that medics could not insert a breathing tube during the 29-minute ambulance ride into Boston. At Massachusetts General Hospital, Dylan had a CT scan and was rushed into surgery, where neurosurgeons removed the left side of his skull and part of the right to stop multiple brain hemorrhages. By the time he was transferred to the neuro intensive-care unit, he was a swollen-faced sphinx—his eyes closed, his head wrapped in bandages, pincushioned with needles, and on a ventilator. His face had been shattered; his left leg was broken. And he was in a deep coma.

To gauge Dylan’s chances of recovery, doctors would rely on standard timelines, and their prognosis would inform treatment. But as neurologists acknowledge, early prognosis is very difficult, diagnosis is often flawed, and the timelines that guide recovery are defied by patients who don’t obey the statistics.

New research also suggests that many seemingly unconscious patients have more consciousness than previously believed and, despite the severity of their injuries, a significant chance of meaningful recovery. Put simply, neuroscience is changing the meaning of “hopeless.”

Day 2

Dylan came from a small town and a big family. To keep everyone informed, his parents, Tracy and Steve Rizzo, issued daily updates on the website CarePages. “Dylan was recently involved in a car accident,” the initial entry began. “He is currently stable, but still in critical condition … The next 3 days will be tough, but he is fighting hard to get through this.”

In the neuro ICU, the definition of consciousness boils down to two conditions: being awake (or aroused) and being aware. A coma is the loss of both of these qualities. One recent revelation is that disorders of consciousness are dynamic—patients can travel back from a coma through a series of way stations that are increasingly well marked, although some are still contested by doctors and researchers.

Day 5

At the ICU, the Rizzos played an iPod filled with Dylan’s favorite music. Some nurses thought Dylan didn’t need stimulation, but it probably didn’t matter. At the neurological level, a coma is like a deep sleep. The unaroused brain is dormant, awaiting a kick from an internal generator. That generator resides in several “arousal nuclei” in the brain stem, clusters of cells barely bigger than grains of salt. When we’re conscious, those clusters are our neural pacemaker, keeping the lights on when we’re awake and shifting us down to sleep.

That same area controls other autonomic functions of the body, such as breathing, heartbeat, and temperature regulation. The gurgling Dylan had made suggested the accident had disrupted the function of his brain stem, which might prevent him from waking up. His doctors wouldn’t know until they could do an MRI, when he became more stable.

Day 8

On the same day as Dylan’s first MRI, neuropsychologist Joseph Giacino administered a test known as the Coma Recovery Scale. He pried Dylan’s eyes open to see if there was any sign of visual tracking. There wasn’t. Dylan scored a 1 on the scale, out of 23.

The director of rehabilitation neuropsychology at Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital and an authority on disorders of consciousness, Giacino had been called in to consult on Dylan’s case. He is among a growing number of experts warning of what he calls a rush to judgment in predicting an outcome for brain-trauma patients. In a study of Canadian trauma centers, researchers reported that one third of the patients who went into the ER with severe traumatic brain injuries died. Half died in the first 72 hours. Nearly two thirds of those early deaths had life support withdrawn, suggesting that the cases were deemed hopeless in the first few days. According to Giacino, it can take much longer than that for a person’s chances of recovery to become clear. Recent literature suggests that if a patient displays any form of conscious awareness within 60 days, his or her chances are considerably better. As a realist, Giacino knows hardly anyone—families, doctors, insurers—can wait that long.

When doctors pored over images from Dylan’s MRI, they were shocked by the damage. In a car accident, the impact sends the brain banging around inside the skull. “It shears or literally tears the axons, the wires that send signals from one part of the brain to the other,” said neurologist Brian Edlow, a member of Dylan’s treatment team. The MRI showed frayed wires everywhere. In his notes, Giacino wrote that “the probability of recovery of functional, vocational, and social independence is low.”

Day 10

Dylan’s family members sat in a conference room with doctors, who showed them the scans. Steve recalled, “They kept saying—it was like 90 percent of what we were looking at—‘This [area] will never recover, this will never recover.’”

“They told us they didn’t think he would ever be able to live at home, that he would probably be institutionalized and have moments of clarity where he would recognize us,” Tracy recalled as tears welled up. “But they didn’t think he would even have that.”

About the only factor in Dylan’s favor was his youth. After the doctors left, Dylan’s father ran out and buttonholed one of them. “Lookit,” he said, “we don’t need time to think. You need to do whatever you can do … What would you do if it were your kid?” He got no disagreement from the doctor, who replied, “We want to do everything.”

Tracy and her sister stayed in the conference room and cried for half an hour. Then Tracy said she told her sister and her husband, “‘When we go out there, we’re not going to tell anybody this.’ And we didn’t. We came out, and [our family and friends] said, ‘How did the meeting go?’ We said, ‘It was good. And we’re going to do everything we can do for Dylan.’”

Day 15

Dylan wore a hairnet of electrodes to monitor brain activity. No poke or prod penetrated his neural darkness, but that didn’t prevent him from “storming,” or displaying what’s called paroxysmal sympathetic activity—brain-injury patients often sweat profusely, spike fevers, and move their limbs spastically. Another disorder causes extreme thirst and urination. His parents read him messages and told him the Bruins had sent him a signed jersey. And they waited.

“We knew that he was not likely to stay in a coma much longer,” Giacino said, “because hardly anybody stays in a coma after 14 days. And then the question is: What do we have at that point?”

Day 17

Dylan opened his eyes.

He’d passed from a coma into a vegetative state, a condition of wakeful unconsciousness—eyes open wide but mind shut down. His brain stem had begun sending pulses of arousal to the rest of the brain, but he still lacked awareness.

For decades, researchers, including Giacino, have found evidence that subtle signs of consciousness are often missed in supposedly vegetative patients. They’ve proposed a new diagnostic category, the minimally conscious state. Many clinicians had regarded both vegetative and minimally conscious patients as “hopelessly brain damaged,” but that view is shifting as technology allows researchers to detect conscious activity in people who show no outward signs of awareness.

Minimally conscious patients are mistakenly diagnosed as vegetative in roughly a third of all cases, according to two studies. “Thirty to 40 percent of people who are believed to be unconscious actually retain some conscious awareness,” Giacino said.

Day 25

One great tension in monitoring a patient’s struggle to regain consciousness is the gap between the expertise of doctors, who observe the patient intermittently, and the observations of the family members, who hover nearby for hours, seeing everything without knowing how to interpret what they are seeing. There was always a family member with Dylan. Tracy quit her job to spend nights with him; Steve, a contractor, left work early. At one time or another, three grandparents and some 70 other relatives maintained a round-the-clock vigil.

Day 27

Dylan had been storming for several days. Tracy and her mother sat at his side, while Tracy wiped sweat off his forehead. Then something remarkable happened: Tracy went to wipe his head, and Dylan raised his hand. When he did it a second time, she put the cloth in his hand and said, “Dylan, wipe it yourself.” He started to wipe his mouth and nose.

Day 33

During his fifth week, Dylan began to show more signs to his team that he was becoming aware of the outside world. His eyes followed a moving mirror. When a doctor pinched Dylan’s nails, he tried to push away his hand. He had passed into the minimally conscious state, instantly increasing his chances of meaningful recovery.

Day 43

How did Dylan’s brain make the transition to conscious awareness? Research suggests that consciousness begins to reemerge when the parts of the brain that receive sensory information reestablish contact with the frontal lobes, which interpret and act on the information. Once Dylan moved from the ICU and into a regular room, the Rizzos tuned the TV to programs they knew their son would like, usually a Bruins hockey game or a Celtics basketball game. One evening, the Bruins were playing, and the two goalies got into a fight. Dylan perked up. “He hasn’t taken his eyes off the TV,” the family reported. “He’s moving his mouth, trying to say something.”

Day 44

Dylan’s doctors performed a second MRI. Remarkably, the scan suggested that some of his damaged wiring had begun to mend. “To our knowledge,” the doctors noted later, “this type of reversal has not been previously described with serial neuroimaging or in a case with such a widespread extent of axonal injury.” The repair process, referred to as plasticity, is much more robust in a young brain than in an old brain, neurologist Edlow explained. One revelation of recent research is evidence that severe injury can activate mechanisms of neural development that normally deploy during childhood.

Day 45

Dylan was still in and out. Sometimes he seemed to pay attention; other times he seemed lost. In mid-February, the Rizzos brought in his Xbox controller. When they placed it in his hands, he stared at it for a few minutes. Then he started to push the buttons and move the joystick. A nurse handed him a tube of ChapStick. He lifted it to his lips. But the biggest breakthrough, to his family, arose from the spontaneous confluence of medical equipment and juvenile humor. Dylan had been tugging at the plastic tubing that connected to his trachea. The family gave him a short rubber tube to distract him. At one point, Steve reached for the other end of the tube and blew into it. The noise sounded like a fart. Dylan laughed. To Tracy, this was a glimmer not only of consciousness but of personality: “We were like, Oh my God! Like, he knew what a fart is, right? He’s still in there!”

Day 45

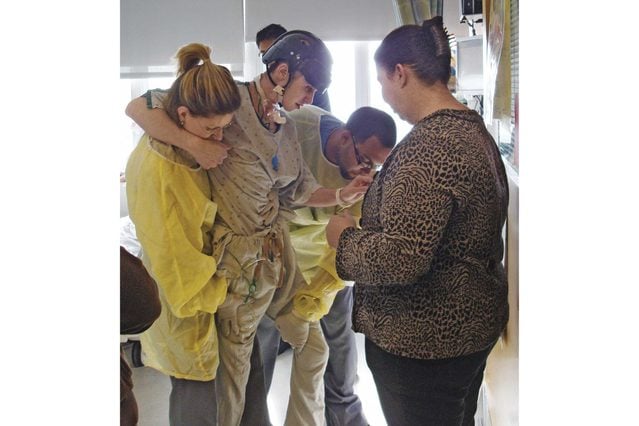

One Friday, physical therapists came in to get Dylan on his feet. Steadied by them, Dylan took a few halting steps toward Steve. When father and son were face-to-face, Dylan reached out, and the two hugged. “Dylan was stroking Dad’s back, up and down, and then patted him on the shoulder,” the family blogged. “You could hear a tear drop.” Emotional responses are another early clue of emerging consciousness, Giacino says.

The following day, Dylan crashed and stormed so badly, there was talk of moving him back into intensive care.

Day 60

At the end of February, Dylan was transferred to Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. Still considered minimally conscious, he could sit up in bed with assistance; he could nonverbally answer biographical questions with about 75 percent accuracy; and he could follow one-step commands about 40 percent of the time.

Day 65

Dylan began to stall. He was agitated and restless. He had bouts of “toning”—muscles in his arms and feet would involuntarily clench until the pain became unbearable, which the family realized when doctors attached a speaking valve to his trach tube so Dylan could vocalize. The first thing he did was cry.

Day 97

At the request of his parents, Dylan was transferred to the pediatric floor. He began to do better. Rehabilitating a minimally conscious brain is a bit like recapitulating childhood. Dylan relearned basic activities: how to stand up, how to walk, how to put on a shirt. Some days he participated avidly; on others, he had no focus.

Day 142

The physical therapy nurses stood Dylan in front of a mirror and wrote “Dylan loves the Yankees” and “Bruins stink” with a marker on the glass. Dylan picked up an eraser and wiped away the insults—“very quick,” his parents reported, “even for Dylan.”

Day 198

Dylan had entered the posttraumatic confusional state. He recognized his dog, but he didn’t know the time or year. He could steer his wheelchair outside (wearing a helmet), but he didn’t know where he was. An MRI showed his white matter continued to heal, but he remained disoriented.

His parents screened movies that Steve called awful but that Dylan had liked: Beerfest. Ace Ventura: Pet Detective. Anchorman. Dylan laughed at the right parts, just as he responded to hockey games when goals were scored. Once, when Dylan appeared to be sleeping, an aunt told his mother a dirty joke. Dylan erupted in laughter.

Day 208

Nurses, patients, doctors, and well-wishers gathered at the reception desk for a send-off party. In a video, Dylan sits in a wheelchair, waving and smiling. His smile has the megawatt quality it had before the accident, but the wave is on a two-second delay, almost slow motion. That day is the first thing he remembers since the day of the accident. “Coming out of it, it was like I was asleep, and I was just back alive,” he said later. “The last day at Spaulding, that’s when I felt alive.”

Before he left Spaulding, he hit another milestone: He said his first word since the accident.

Day 271

Dylan spent two months at another rehab center before returning home. He began to walk with a walker and could climb a few steps, but he struggled with cognitive tasks. A brain scan on day 366 confirmed the extent of his recovery and the permanence of other injuries. In the left frontal lobe, some tissue had atrophied and would never come back. Still, at a fund-raiser in July, he danced.

Day 746

Dylan went rock climbing, working his way up a climbing wall. The Rizzos sent the video to Giacino, who includes the clip when he gives talks about recovery in patients who reached a minimally conscious state within 60 days of their injury. It is a vivid embodiment of his argument for patience. “What this tells us,” Giacino said, “is that the story doesn’t end at 12 months.” Dylan is among a growing number of patients who defy the odds. “We don’t know how many exceptions to the rule there are,” Giacino said. “So I don’t believe in the rule anymore.”

Day 1,541

“It’s impeccable,” Dylan was saying. We were sitting in the Rizzo home, and he was describing his bedroom. His mother talked about how her son had changed. “He’s still the same person,” Tracy said. “Just neater. He was a slob before the accident.” Dylan smiled.

The most conspicuous reminder of his injury was a slight indentation in his left temple and two shiny lanes of hairless skin that run back from the crown of his forehead. Now 23, he is functionally independent. He volunteers as an assistant track coach at his old high school, helps his father on construction projects, and hopes to attend community college. He continues to need speech and cognitive therapy. “Dylan still has memory issues, organization issues, and time-management issues,” Tracy said. He does not remember a single thing about the six months prior to the accident or the seven months after.

Not only is he functional, but he’s functional in a red-blooded 20-something way. When we went out for lunch, Dylan ordered a sampler of microbrews (“His neurologist says he can have one or two beers,” Tracy said). Back at home, I asked to see his room. Dylan effortlessly climbed the stairs and led me there. Inside was a flat-screen TV, and a lacrosse stick was propped in one corner. The bed was made, and Steve opened the closet to reveal T-shirts, each hung and color-sorted. “There was nothing in here before the accident. Everything was on the floor,” he said, then laughed. “Reprogramming the brain works.”