Doctors Explain Aphasia: The Brain Condition Leading Bruce Willis to Retire from Acting

Updated: Apr. 03, 2022

A renowned neurology physician and researcher provides insight on aphasia, including its causes and symptoms; while speech experts explain how Willis's family may play a key role in his treatment.

What is aphasia?

For decades, Bruce Willis has been known as one of the most dynamic action stars on the screen. But on Wednesday, word broke that Willis, 67, will retire from acting due to aphasia, a brain condition that can impair an individual’s ability to speak, understand, read, or write.

The announcement came via the Willis family, including Demi Moore (to whom he was married from 1987 to 1998; they share three daughters and a friendly co-parenting relationship), who together shared on Instagram:

“To Bruce’s amazing supporters, as a family, we wanted to share that our beloved Bruce has been experiencing some health issues and has recently been diagnosed with aphasia, which is impacting his cognitive abilities. As a result of this and with much consideration Bruce is stepping away from the career that has meant so much to him.”

The family’s heartfelt announcement is drawing attention to aphasia, a condition that affects more than two million Americans, according to the National Aphasia Association. “Aphasia is an acquired problem with communication,” Roy Hamilton, MD, tells The Healthy. Hamilton is an associate professor in the departments of Neurology and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he also directs the Laboratory for Cognition and Neural Stimulation.

“Should I be worried about my loved one?” 6 Signs Your Family Member’s “Forgetfulness” Is Actually Alzheimer’s Disease

Aphasia causes

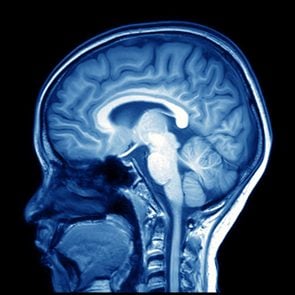

The brain’s left hemisphere is in charge of processing language, Hamilton says. “Anything that injures or insults this portion of the brain can potentially cause aphasia.”

Aphasia causes may include a stroke, head injury, tumor, or infection on the left side of the brain. (Though this hasn’t been confirmed, media reports have suggested that Willis sustained multiple head injuries over the course of his acting career—which, if true, could possibly have led to the diagnosis.)

Hamilton adds that as many as 40 percent of people who survive a stroke will have some degree of aphasia. “It can also happen as a result of a progressive neurodegenerative disease. This is known as ‘primary progressive aphasia.'”

Cold Weather, Heart Attack, and Stroke: 3 Heart Doctors Share Their Insights on Staying Safe

Types of aphasia

There are several different types of aphasia. They are categorized based mainly on what specific part of the brain is affected, and what symptoms the condition produces.

The main types of aphasia include:

Broca’s Aphasia

With this form of aphasia, a person may understand speech and know what they want to say, but will speak in short phrases that take significant effort.

Wernicke’s Aphasia

People with Wernicke’s aphasia may speak in long, complete sentences that make no sense.

Primary Progressive Aphasia

This is the result of a neurodegenerative brain disease.

Global Aphasia

This is the most severe form of aphasia. Individuals who have global aphasia are unable to produce many words and will understand little or no spoken language.

Aphasia symptoms

Aphasia symptoms can range from mild to severe, affecting the ability to speak, understand, read, or write. The patient may not be able to think of the words you want to say, or may say the wrong word at the wrong time. Some people with this condition will use made-up words and string them together with real words, forming nonsensical sentences (Wernicke’s Aphasia).

In addition, aphasia can affect your ability to comprehend what others are trying to say. Reading, writing, and the ability to do math can also be difficult.

Diagnosing aphasia

To diagnose aphasia, most patients will undergo imaging tests of their brain to see what part is affected. Elizabeth Galletta, PhD, clinical associate professor of rehabilitation medicine at NYU Langone Rusk Rehabilitation in New York City, explains that speech and language therapists are usually called in to assess receptive language or how well the patient understands expressive language, or how well they use words to express themselves, along with reading and writing.

Aphasia treatments

“Treatment typically involves speech and language therapy, and depending on the cause of the aphasia, progress is possible,” Hamilton says. “People who develop aphasia following a stroke can have some degree of improvement over time, and some individuals with more modest deficits after a stroke may recover to a point where they have no function deficits of communication anymore.”

Others may have persistent deficits. “The field still lacks targeted neurologic therapies that directly affect how the brain functions,” he says.

There are some promising treatments in the pipeline that could help people like Willis in the future. Some researchers are using noninvasive brain stimulation with speech and language therapy to see if changing brain activity could allow people to re-learn language skills.

There are different ways to activate parts of the brain to amplify the benefits of speech. Brooke Hatfield, associate director of Health Care Services at The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association in Rockville, MD, says, “One premise is that we can turn off a part of the brain that is interfering with the side that controls language, and another premise is to recruit as much chemical activity to the part of brain responsible for speech and language.” Exercise is also helpful for people with aphasia. “Physical activity helps the brain recover, too.”

Speech therapy for aphasia is usually aimed at improving or restoring lost function or learning how to better compensate for it, Hatfield says, while restorative therapy targets a problem area such as word-finding. “We create a structured activity to help think of the word and then lay on cues to get them there and make a connection.”

And, she says, it works. “If aphasia from an acquired disorder such as stroke or brain injury, it responds really well to therapy and improves over time.” She notes that “if it is a progressive problem, it’s not going to improve.” In these cases, she suggests, therapy can help people prepare for the future.

With compensatory therapy, a speech therapist may help you discover other ways to express ideas when you have trouble talking, such as pointing, drawing, or using a computer. “A compensatory mechanism is not restoring your access to terms, but working on conversational techniques to compensate for the loss,” Galleta says, adding that this often involves working with the entire family. “The listener can give choices of words to help the person express themselves.”

The bottom line? “People with aphasia can make gains during therapy,” says Galleta. “It’s not a quick fix, but people who work hard in treatment can improve their communication skills and lead happy, healthy lives with aphasia even if it is progressive.”

Sign up for The Healthy @Reader’s Digest newsletter for brain health insights and much more. Follow us on Facebook and Instagram, and keep reading:

- The 10 Best Health Books of 2022: Therapists and Readers Rate the Bestselling Wellness Books So Far This Year

- This Is Your Brain on Sugar: A Dietitian Details How a Love for Sweets May Worsen Your Memory

- The New COVID-19 Variant, “BA.2″—9 Facts, Straight From Medical Specialists

- Doctors Discuss Alopecia and 9 Other Scalp Conditions That Call for Greater Awareness