Kids Who Count with Their Fingers Are Smarter, Researchers Say

Updated: Mar. 13, 2017

The more aware students are of their individual fingers, the higher they score on math tests.

If you were like most kids, your mother told you there were three no-no’s when it came to your fingers: Don’t put them in an electrical outlet, don’t stick them up your nose (at least not in public), and don’t use them when you’re counting. The first two laws of finger dynamics are as true as ever. But experts in education and cognition now believe that using your fingers to do math is not only a perfectly good idea but may even help children become superior students. (Is the American school system damaging our kids?)

If you were like most kids, your mother told you there were three no-no’s when it came to your fingers: Don’t put them in an electrical outlet, don’t stick them up your nose (at least not in public), and don’t use them when you’re counting. The first two laws of finger dynamics are as true as ever. But experts in education and cognition now believe that using your fingers to do math is not only a perfectly good idea but may even help children become superior students. (Is the American school system damaging our kids?)

It certainly makes sense. When children count on their fingers, they take an abstract concept—mathematics—and translate it into the most basic, tangible form. In fact, neurobiologists believe that the brain is hardwired to “see” a representation of our fingers even when we aren’t literally counting on them.

There is a section of the brain, called the somatosensory finger area, that activates when we respond to heat, pressure, pain, or the use of a given finger. Studying brain scans, researchers discovered that when students ages 8 to 13 work on subtraction equations, the somatosensory region “lights up” on the scans, even if the students aren’t using their fingers. The more complex the subtraction problem, the more activity is detected in the somatosensory region. The researchers theorize that when the brain is called on to subtract, it automatically marshals its finger-counting ability to get the job done, regardless of whether any actual fingers are doing the counting. Try these other activities that boost your brain power.

The connection between finger use and math ability has been demonstrated on old-fashioned math tests as well. With their eyes closed, first graders were asked to identify which of their fingers a researcher was touching, along with other finger-related exercises. A year later, the students who scored highest on the finger-ID questions consistently scored higher on a math test. When college students were given the same finger quiz, the highest scorers once again performed best on calculation tests.

So what does all this mean? For one thing, parents and teachers shouldn’t discourage children from counting on their fingers. “Telling students not to use their fingers to count or represent quantities is akin to halting their mathematical development,” says Jo Boaler, PhD, a professor of math education at Stanford University. (This discouragement may be more rampant than you think—a 2014 mailing from Kumon, a nationwide tutoring service, carried an article titled “Why Finger Counting Is a No-No!”)

Researchers at Stanford also stress that some students simply learn better using visual tools rather than by memorizing the multiplication tables and reciting them as quickly as possible. “When I introduce math problems to my Stanford students, I say, ‘I don’t care about speed; in fact, I am unimpressed by those who finish quickly. That shows you are not thinking deeply,’” says Boaler. “Instead I would like to see interesting and creative representations of ideas.”

Boaler believes that anyone—at any age—looking to improve his or her math ability would do well to improve basic finger dexterity. That means not only counting on your digits but also sharpening general finger “perception.”

That may sound simplistic, but the researchers at Stanford offer an interesting anecdotal hypothesis: “The need for and importance of finger perception could even be the reason that pianists and other musicians often display higher mathematical understanding than people who don’t learn a musical instrument.”

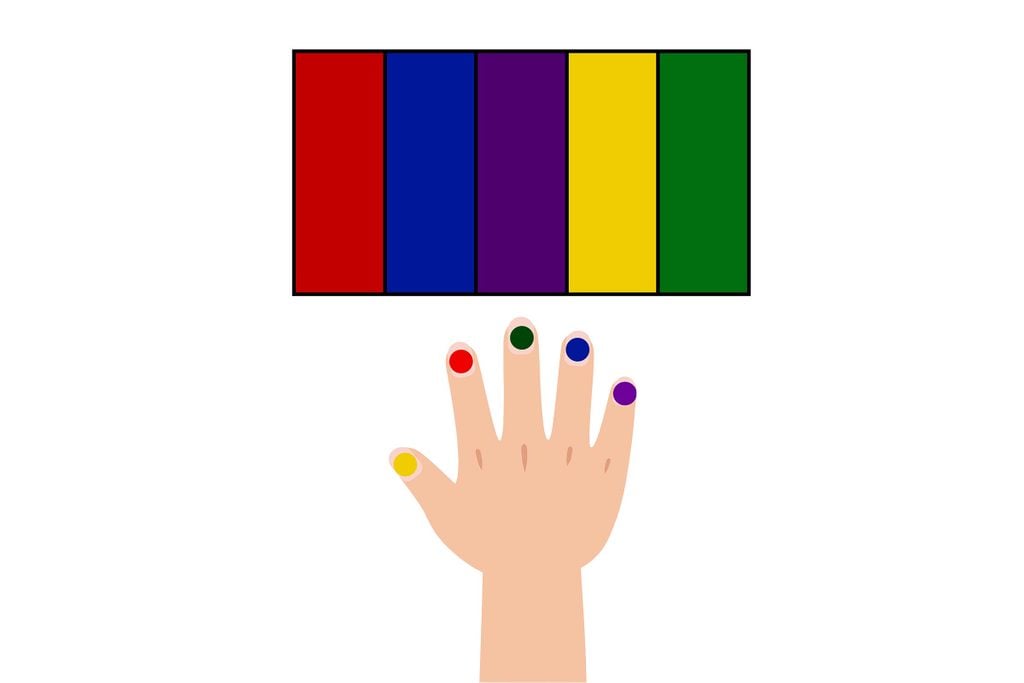

To that end, Stanford’s Youcubed center, which develops resources for math teachers, has devised a series of activities to strengthen students’ perception of their fingers. We’ve included one of them here (see below) for you to try at home. For keyboard templates and more activities, go to youcubed.org.

The Piano Exercise

You’ll need a series of paper “keyboards” like the one above, each with the colors in different spots. Put a colored dot on each finger, as shown. Starting with the key on the far left, touch the corresponding finger to each colored “piano key” and hold for a few seconds. Work through all five keys. Switch hands, then add new keyboards.