How Luke Russert Knew It Was Time for a Career Change: ‘There Was Something Missing’

Updated: May 08, 2023

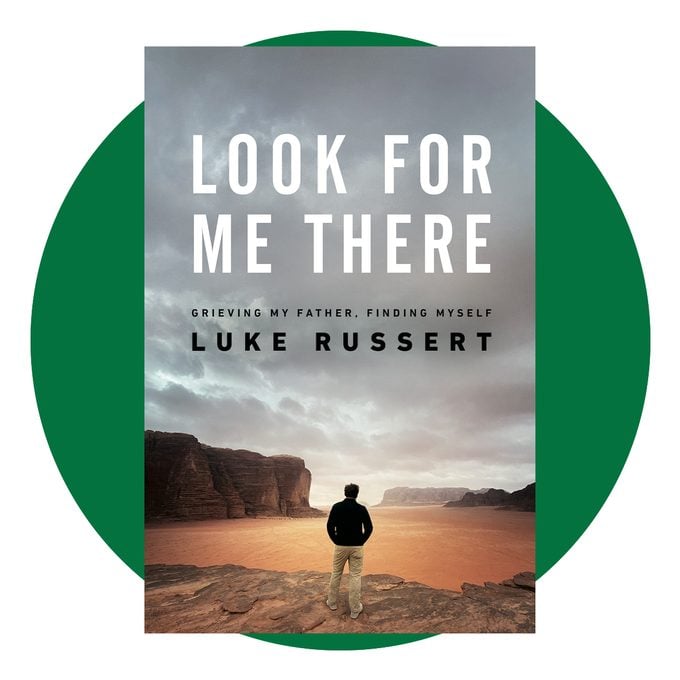

Emmy-winning Washington journalist Luke Russert spotlights untapped mental health themes in his breakout memoir, Look for Me There.

Our editors and experts handpick every product we feature. We may earn a commission from your purchases.

When revered television journalist Tim Russert passed away in 2008, his son Luke, then in his early twenties, was uniquely poised to step into the spotlight the elder Russert had created. Luke Russert had been part of an Emmy-winning team at NBC News and was gaining major reporting chops in his own rite when in 2016, he announced his decision to step away from his TV career.

In May 2023, Russert debuts his first memoir, Look for Me There: Grieving My Father, Finding Myself (Harper Horizon), which details the subsequent search for meaning that took him on a near-four-year journey to 65 countries. The Healthy @Reader’s Digest spoke one-on-one with the Washington, DC native and die-hard Buffalo Bills fan, whose evolved introspections suggest it may be high time for an Eat Pray Love era among Western men.

Experts Say Most People Who Live to 100 Years Old Share This One Thing in Common

The Healthy @Reader’s Digest: Luke, just look at the “Great Resignation“—in recent years, a lot of people have decided to put their health and personal needs ahead of what can feel like the overwhelming demands of career. In an especially fast-paced environment like journalism, that can be a really tough decision. What brought you to it?

Luke Russert: I think you touched on something, which is very true—which is that more so than any time in human history, because of how technologically advanced we are, it is impossible to unplug literally and figuratively. I was in media at a time … when there was a lot of stuff going on the Internet, and Facebook was just starting to become a powerhouse in the news world. And then in the blink of an eye around 2010, 2011, everything sort of migrated over to Twitter, which not only grew the pool of folks who were quote-unquote reporters, but it also made it nearly impossible to turn off.

I had reached a crossroads in my early thirties where I was seemingly on a path to have everything one could want. I had a successful job. I had a name recognition. I was moving up in the media world. There was tons of opportunity in a lot of different areas, but I wasn’t fulfilled. There was something missing and I couldn’t quite point my put my finger on it. But I knew that if I stayed in the same place, if I stayed on the proverbial hamster wheel, so to say, that nothing was going to change—that the only way that I could change internally was to change the external, which was to get out of Washington. Honestly, when I started, I didn’t know how long it’d be—I thought maybe six months.

But what I found was that once I was able to distance myself, take a breath, be away from the weight of expectation, be away from the, You shouldn’t be doing this, you need to be doing this, and actually taking a moment to say, OK, what do I want to do? Where can I be most productive? What is my passion? And where can I contribute in society? Or where is a place where I’m not going to feel anxious or where I’m going to be content and full and happy? It took me a while to get there. It took me a lot longer than I thought when I started it. But it was a very important journey because ultimately it brought me to a place of peace.

The Healthy: Your dad was a giant to a lot of people. What role did losing him play in your decision?

Luke Russert: I think for me with grief was he died so unexpectedly, and it’s cliche, but I think it’s very true: When you lose a parent at a younger age, you grow up really fast, almost seemingly overnight. There are things that are put into your orbit, which you might not know how to deal with, that you are uncomfortable with. The first thing is your relationship with the surviving parent changes in some capacity because whether you’re an only child like I am, or you have siblings, that parent now is more dependent on you than they were before, more likely than not. Then you add in just the sort of what I would call the process of the death, which a lot of people don’t get when it’s unexpected, which is that you’re dealing with the coroner and the funeral and this sort of fallout that you get wrapped up in. And the idea is, OK, I’ve got to make sure I get through this eulogy and this service, and then I’ll relax after that.

And I think in my case, I never really took a moment to relax. It was sort of finding a cure for misery in the work, in having something to do. And while that can be beneficial, it can also be all-consuming. And what I ended up doing was sort of internalizing it and not being conscientious of when the trauma would rear itself, and ignore it. So to the outside world, I would put on a very jocular, strong sense of bravado, sort of like my little shield. I’m smiling, I’m laughing, I’m above it all, I’m having a good time—Don’t worry, I’m all good. But that was a lot of times covering up for internal pain that I didn’t want to face, because facing it is hard. You can’t admit weakness if you’re a man—that’s what society tells you. Or you have to go to these places that are very uncomfortable to be in, and you have to sit in them. And the first thing in my opinion, in terms of processing grief, is you have to learn how to sit in it for a long time and understand, OK, I can’t escape it, so let me sit in it and try to work my way through it and understand it and see what it reveals.

And ultimately, that took me a number of years, but once I was able to do that, it became a lot more clear. I [realized], “Yeah, it’s part of life.” I would always say to myself for so many years: “Well, there’s so many people who have a lot worse than me and don’t feel sorry for yourself. You’re so privileged.” And retrospectively, that’s true, but it’s not honest because there is pain. And it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from, the pain is real and so true. If you don’t process that pain, it never goes away. And it’s going to limit your life and what you’re able to accomplish and ultimately how you feel.

The Healthy: We need younger male voices saying this.

Luke Russert: You’re touching on something I get at, which is there’s all this talk about radical vulnerability now. I think vulnerability is important, but it’s extremely important for men. We’re taught not to be vulnerable. And that’s changing, thankfully. I think our generation was sort of the first generation to [uphold] male figures who are nicer, who would allow you to cry a little bit. But it’s still an uphill battle. I didn’t show emotion and I didn’t want to show emotion, and I tried to hold back a lot of those feelings, and that was because I saw a vulnerability as uncomfortable. I saw it a lot of times as weak: If you’re going to have a moment, then go do it by yourself. Don’t show the world. And that’s something where there’s gotta be a better balance.

The Healthy: Was your dad an expressive person?

Luke Russert: It’s very interesting. He, and obviously my grandfather—World War II generation—they never really expressed much emotion. My father always knew his dad loved him, and there was always that bond, but it was often done through action, not words. My father made it a point to be more emotive with me. And I knew that he loved me and he would say as much when I was a young kid, and he was very supportive and he always had my back. But in terms of his own emotions, I mean, he kept those very much inside. I only saw him cry on a few occasions—and they most always had to do with his dad, interestingly enough. So my dad held a lot of that in and I’ve often wondered about that because it could not have been easy for him to do that.

But that being said, I think what brought him great joy was helping others. I was floored after he passed: So many people reached out to me telling me stories of, “I was in a difficult place and your dad helped me out.” Or, “I was unsure of something, and your dad talked to me and he checked in on me.” And I always sort of thought like, OK, that was his way of helping people. But also I think in some ways, it was therapeutic for him. It was his sort of way of understanding, OK, a lot of people are going through difficult times, or that there’s a sort of commonality in the human struggle.

The Healthy: Tell us about your adventures—fill in the blank: Travel was _______ in my journey of healing.

Luke Russert: I have two, is that OK? It was illuminating, and it was liberating. I think especially when you travel to more places and you go to some more exotic places and you go to places that aren’t as developed as the US or in places in Europe, it kind of strips away a lot of the pretense. So a little bit is, OK, who am I right now? I’m not Luke from Washington, DC, where people know me. Now I am just Luke, right?

Being away from the world, I knew, while it was exciting and exhilarating, sometimes there was loneliness. But within that loneliness, I was able to really have real time of self-reflection. And I think that’s what the travel really does for you: It gives you some time to reflect, not only on how other people are encountering things or doing things, but also, Here I am, a little bit untethered from my past life. Let me explore myself a little bit.

The Healthy: That’s a good point, especially coming out of the pandemic when so many people experienced stretches of alone time. Also recent research suggested that relationships are the key to good health and longevity. But what about the benefits of solitude?

Luke Russert: I think that I would probably agree with that study, that relationships are so very important and we all need one another at some point, right? You want that bond. You want someone to pick you up. You want to be able to pick up another person. My dad used to always say, “The greatest exercise for human heart is picking somebody else up.”

However, I do think there is a power of aloneness, and I write about that. This came to me at a pig farm in Nicaragua of all places where I was by myself, and I was literally sleeping on straw and dirt in a concrete cell. It was a cheap place, it was just sort of easy to stay. And I sat there and was contemplating a lot, but what I realized was, I’m OK. Here I am by myself in this foreign place, and I’m getting by just fine. And that to me is something that really only comes by being alone for some period of time and learning how to be alone. It’s sort of a way to train or prep for any type of situation that’s going come forward in your life. Because if you are comfortable being alone and you can be alone, and you understand it in your mind is in control, it’s not playing tricks on you, to me, you’re unbeatable. I think that’s something that’s an important skill to have.

It’s not for everybody. There are some people who are very social beings, and they need to be. And you know, it’s interesting. You often see them if they experience a great tragedy in their life, they put themselves out there, they take up different hobbies. I think my mom’s kind of like that, to be honest with you. She can be alone. She understands that—but she loves people and she loves engaging in different projects and working and being around and traveling. But that ability to sit by yourself within your own thoughts and be comfortable there is something which, if you can master, you’ll be very happy in life. You’ll be very content.

Get The Healthy @Reader’s Digest newsletter and follow The Healthy on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. Keep reading:

- I Walked Everywhere I Needed to Go for a Week—Here’s What Happened

- This Emotion Is Worse for Your Health Than Junk Food, According to a Leading Functional Medicine Doctor

- What Is Medical Gaslighting? 9 Doctors’ Statements That Are Major Red Flags

- The 12 Absolute Best Commuter Bikes & E-Bikes for Getting Around in 2023, from Industry Experts and Bike Enthusiasts