Have a Friction Blister? Here’s How to Prevent and Treat Blisters

Updated: May 13, 2021

Friction blisters occur from repeated rubbing or pressure on your skin, and you can get them on your palms, heels, soles, fingers, and toes. Here's what you need to know about preventing and treating blisters.

On This Page

What is a friction blister?

If you’ve ever decided to break in a new pair of shoes by going for a long walk or run, you may have been sidelined by a painful friction blister. These fluid-filled bubbles develop on the outer layer of your skin from repeated rubbing (friction) at one particular spot. Other terms for friction blisters are “vesicles” for smaller blisters and “bulla” for a larger one.

Friction blisters usually get better on their own without any issues, but there are things you can do to treat and prevent them. It’s also important to know when to contact your doctor about a troublesome blister. (Here’s how to get rid of blisters on feet.)

Friction blister symptoms

Friction blisters tend to appear on your palms, heels, soles, fingers, and toes. “They are likely to occur in areas where there is lots of movement and friction plus damp skin,” says Brittany Smirnov, DO, a dermatologist in Delray, Florida. “If you are extremely sweaty or just got out of the bath or shower and throw on your shoes to go for a run, you will most likely develop a friction blister on your foot.”

Such friction also can cause a diabetic blister if you have diabetes. The most common spot for a friction blister is the back of your heel where it rubs against the shoe, she says.

Friction blisters can occur in people of all ages, but tend to happen often in people who walk or run a lot. This is why friction blisters are extremely common in hikers, soldiers, and elite athletes such as ultramarathon runners.

Your doctor can diagnose a blister simply by looking at it. Lab tests are rarely needed. These raised, fluid-filled bubbles can be painful, especially if you continue performing the activity that caused it to form. Don’t continue your run if you notice the telltale pain and irritation in your heel, says Dr. Smirnov. If you put pressure on the blister, it can spread and become larger, she says.

Friction blister causes

A friction blister forms where the skin is weakest. “As skin rises up, it becomes weaker so when friction occurs, there is a breakdown of the weak skin and clear fluid fills the space,” explains Dr. Smirnov.

So what exactly is inside a blister? This fluid is called serum. It is what remains of blood when red blood cells and clotting factors are removed. (Plasma is the clear, watery portion of the blood after the blood cells have been removed, and serum is the clear liquid left after the blood clots. If its dark red, purple, or even black, it could be a blood blister.)

“The fluid is serum (water, protein, carbs), which comes out of the leaky or injured blood vessels that are damaged from the friction,” explains Adam Friedman, MD, professor and interim chair of dermatology in the department of dermatology at George Washington School of Medicine and Health Sciences in Washington, D.C. This build-up of fluid is what splits the skin layers, creating a blister.

And the serum actually serves a purpose. The fluid cushions and protects the underlying tissue from damage so that it can heal.

Friction blister treatment

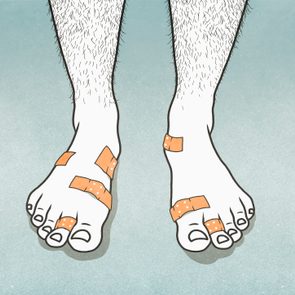

Most friction blisters will heal on their own in one to two weeks. If the blister doesn’t pop, the fluid reabsorbs and the damaged skin peels off. You can place a bandage over the blister to keep it clean and stave off a potential infection, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) suggests.

“Just be careful when you take it off so you don’t rip off the protective skin,” Dr. Smirnov says. Unlike blood blisters, it is OK to pop a friction blister if you do so carefully with a sterilized needle or safety pin, Dr. Smirnov says.

However, popping a blister does expose the area to a risk of infection. You may want to avoid popping a blister unless it is large and painful—it’s best to let them heal on their own. (If you have diabetes, circulatory problems, or other health issues, don’t attempt to pop your own blister—talk to your doctor about what to do.)

That said, if you need to pop a blister, sterilize the needle at home by soaking it in alcohol, holding it against a lit match and/or placing the item in boiling water. Wipe the blister down with iodine or rubbing alcohol before attempting to pop it, she says. Make sure the pin or needle is dry and cool before using it. “Pop it at the lowest gravitation point or bottom so all the fluid can fall out according to gravity,” she says.

Don’t remove the skin that covers the fluid. “The skin serves as a natural bandage and helps prevent infection,” she says. “As soon as you remove this roof, you are exposing the area to possible infection.” If you only pop the blister and leave the skin intact, there will just be a small hole that is exposed and it is much less likely to become infected, she explains.

Dr. Friedman adds that the area should be covered with a barrier protectant such as Vaseline or paraffin wax and covered to enable healing and protect the area from infection.

When to see a doctor

It’s important to be on the lookout for signs of infection if you develop a friction blister. “This may include warmth or redness around the blister,” Dr. Smirnov says. “The fluid should always be clear. If you ever notice pus, see your dermatologist.” Infections may require antibiotics, she explains.

If you know what caused your friction blister, it’s likely nothing serious. But “if you are getting blisters on your hands and feet without a known causative incident, see a dermatologist to find out what else may be going on.”

Certain diseases and/or medications may cause blistering. For example, pemphigus is a rare, blistering skin disease that can occur in middle-aged and older adults, and pemphigoid is a blistering autoimmune disorder that is more commonly seen in older adults.

How to prevent friction blisters

If you are a pro athlete, weekend warrior, or if your job has you on your feet or requires you to use your hands all day long, an ounce of blister prevention goes a long way.

For starters, keep your skin clean and dry at all times. “Always stretch out your shoes before a big run or wearing them for extended periods of time,” she says. Make sure your shoes fit properly as well,. Nylon or moisture-wicking socks can keep your feet drier and less prone to friction blisters. (The AAD suggests wearing two pairs to protect your skin.)

If there are areas that are prone to blisters, consider covering them with soft bandages or moleskin for added protection. “Applying petroleum jelly to problem areas will reduce friction when your skin rubs together or rubs against clothing,” Dr. Smirnov says. “This acts as a nice barrier.”

Also, consider using gloves or other protective gear on your hands if you use tools or sports equipment that causes friction. Knowing the warning signs can help too. If you start to feel pain or notice your skin turning red, stop the activity at once.

If you are prone to blisters, keep moleskin or bandages handy. “It’s also good to have petroleum jelly on hand to cover an area that is prone to friction blisters,” Dr. Smirnov suggests. Trying an anti-friction stick or balm to help reduce the risk of a blister is another prevention option.

(Next, learn the difference between a fever blister and a cold sore.)

Additional resources

For more information and help on friction blisters, here are a few more resources: