How to Use a Pain Scale to Assess Your Pain

Updated: Mar. 09, 2021

A pain scale is a useful tool that helps you communicate to your health care provider how you're feeling.

Measuring pain

If you’ve ever had a painful injury or dealt with chronic pain, your health care provider may have asked you to describe it: Is it sharp or dull? Sudden or ongoing?

The hardest of all to answer, especially to a stranger like a nurse or a doctor, can be, “How bad is it?”

Trying to explain your pain can be painful itself.

“Pain, for the most part, is a subjective experience,” says Gregory A. Liguori, MD, director of the department of anesthesiology, critical care and pain management and anesthesiologist-in-chief at the Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) in New York.

To better communicate the level of pain you’re experiencing, pain scales give patients and doctors a way of talking about a subject that can often be hard to explain.

(Here’s more on how pain management specialists can help you treat chronic pain.)

The difficulties of assessing pain

It’s not just challenging for the patient to describe what they’re feeling: It’s hard for the physician to assess it as well.

“If a patient says their blood pressure is elevated, a clinician can measure their blood pressure with a cuff, and confirm or refute that assertion,” Dr. Liguori says.

“On the other hand, if a patient says they are in pain, who is to say they are not? There may be some collateral signs such as a look of anguish on someone’s face, or an elevated heart rate or blood pressure,” he says.

However, he adds, “for the most part, when a patient says they have pain, in most cases, they should be believed.”

(Here are the pain medications doctors avoid.)

What is a pain scale?

To help doctors and nurses better understand their patients’ pain, pain scales were developed over the last century.

“Pain scales create a standardized way for clinicians to assess a patient’s pain experience or feelings of discomfort during their treatment for an acute or chronic illness,” says anesthesiologist and pain medicine physician David Dickerson, MD, chair of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Committee on Pain Medicine.

“These tools use patient responses or clinician observations to evaluate a patient’s pain or the impact of the pain on function,” he says.

Although many of these tools were developed for use in research studies to measure how subjects were feeling, he says, today they are widely used by health care workers to determine patient care as well.

Pain scales are “essential in managing both acute and chronic pain,” Dr. Liguori says.

Because of the nebulous nature of pain, “having a quantitative scale that can assess how much pain someone is experiencing is quite important. These scales are widely used and provide the basis for assessing pain and guiding caregivers as to the efficacy of pain treatment options.”

Different pain scales for different purposes

But there isn’t just one universal pain scale.

“Pain scales are validated or confirmed for accurate use in specific groups of patients such as children, adults, and non-verbal or non-interactive patients,” Dr. Dickerson says.

Dr. Liguori also says that different scales work better in different populations of patients.

Here’s a closer look at the main types of pain scales used by health care workers and researchers.

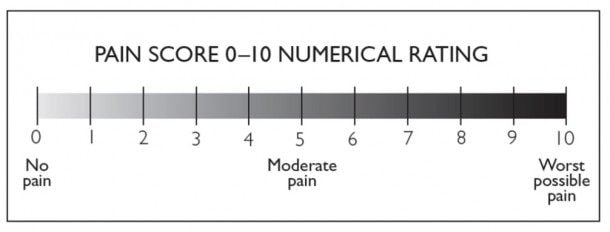

Numerical Ratings Scale (NRS)

The most commonly used pain scale is the NRS or numerical rating scale. Doctors ask their patients to rate their pain from 0 to 10 with 0 being no discomfort and 10 being the worst pain imaginable, Dr. Dickerson says.

In a 2018 review of research published in the Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, the NRS was found to be the optimal response scale to evaluate pain among adults without cognitive impairments.

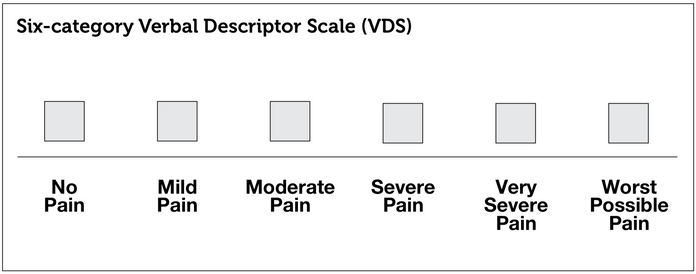

Verbal Ratings Scale (VRS)

The Verbal Ratings Scale is similar to the NRS but is even simpler. People are asked to rate their pain on just four levels: none, mild, moderate, and severe.

This might be easier for elderly or cognitively impaired adults to understand. In addition, a 2018 study in the Annals of Emergency Medicine of more than 700 children found it to be a valid way to measure pain for children over 6 years old.

A similar tool is the Verbal Descriptor Scale (VDS), which also may include the categories of very severe (or extreme) pain, and worst possible pain.

Yet another adaptation of this scale is the Iowa Pain Thermometer, which combines these categories with a visual representation of a thermometer and is often preferred by older patients.

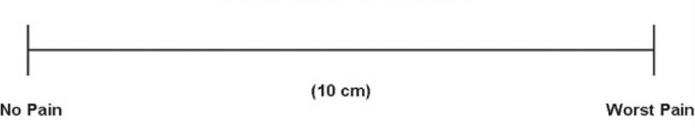

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

The Visual Analog Scale or VAS shows a line with “no pain” on one end and “worst pain” on the other end.

Instead of assigning a number in your head to your pain, you pick a spot along the visual line to show where your pain ranks, somewhere between comfort and severe pain, Dr. Liguori says.

In one 2019 review of research on low back pain published in the Journal of Pain, no evidence was found that either the VAS or the NRS was the best way to measure pain; but the researchers noted that more research is needed.

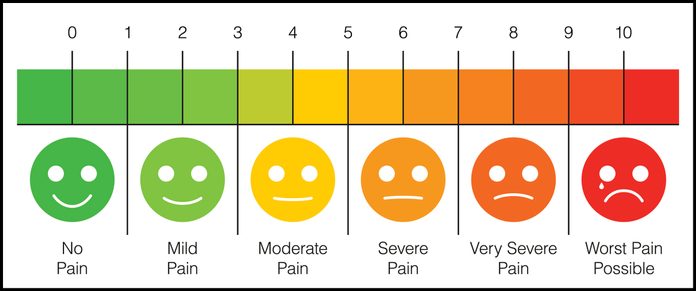

Face Scale

This visual scale was developed in the 1980s and features a series of cartoon faces ranging from a happy, smiling face and ending in a crying, grimacing face.

“In the case of children we have them select from pictures of different faces expressing varying amounts of comfort or distress the image that best shows how they feel,” Dr. Dickerson explains.

Because children’s use of language is not as advanced as that of adults, young patients may be able to better recognize a visual representation of the emotion they’re feeling.

Functional pain scales

Scales like the NRS and the Faces Scale are subjective pain scales because they are based on how the patient reports their feelings, Dr. Dickerson says.

In contrast, functional pain scales are more objective and incorporate how pain has an impact on a patient’s activities.

For example, you might choose that your pain is level “3” but you’re able to read, watch TV, and talk on the phone. Or you might choose that your pain is “4” and you’re unable to do any of those activities.

Instead of asking patients to rate their pain based on an abstract concept of best to worst, functional pain scales assess the pain in more concrete terms of how it affects the things you do in your daily life.

Limitations of pain scales

Although measuring pain in one or more of these ways can be helpful, these pain scales have shortcomings.

Pain scales have two main limitations, according to Dr. Liguori.

“The first is the interpersonal variability in pain responses: If you prick your finger on a thorn, one person may rate that a 2, mild pain, and another person may rate that as a 9, severe pain—each patient perceives pain differently,” he says.

“The second limitation is that there is no way to independently validate one’s response to the scale,” Dr. Liguori says.

“If a patient says their pain is a 10, they should be medicated with an analgesic [pain reliever]. Maybe that person truly is in pain, but maybe they are seeking pain medications for secondary reasons.”

(Here’s what doctors should tell you about pain meds.)

Another limitation, Dr. Dickerson says, is that people with chronic pain may have an improved ability to function, but their pain may not get better.

Pain scales are just one tool of many

Because pain scales have their drawbacks, they’re never just used alone.

“These scales are one component of a more comprehensive patient assessment, and are typically used in combination with a broader clinician evaluation that assesses other subjective and objective findings,” Dr. Dickerson says.

“These may include vital signs, physical examination, and historical information that is either reported or observed, such as tolerance of coughing, deep breathing, walking, sitting, standing, or other activities of daily living.”

(Looking to try CBD for aches? Here’s what to know about CBD oil for pain.)

How health care workers use pain scales for treatment

Even with their limits, pain scales can be helpful both for acute and chronic pain situations.

One reason to use them is to determine when and how much to medicate a patient in pain, Dr. Liguori says.

“For example, when a patient awakes from surgery, the PACU [post-anesthesia care unit] nurse will ask them about their pain using the NRS. If the patient says their NRS is a 0, no pain medication will be offered, as it is not needed,” he says.

However, if the patient says their NRS is a 3-4, then the nurse may discuss a small dose of pain medication. If the patient says their NRS is a 9-10, the nurse will likely start some pain medication quickly.

(These are the pain symptoms to never ignore.)

Dealing with an unexpected response to a pain scale

Dr. Dickerson points out that if a patient responds unexpectedly to a pain scale, it could signal something is wrong.

“If a patient reports no pain on a pain scale after a significant surgery or injury where some degree of pain is expected, this could be a sign of overmedication, an underlying cognitive issue such as delirium, or a failure to understand the pain assessment being used,” he says.

As patients start to heal, pain scales typically tend to reflect this and pain medications are reduced.

But treatment plans may need to be re-evaluated and adjusted if there aren’t changes in how a person reports pain. Pain scales can also identify developing issues or complications.

Over time, continued assessments can create a path to recovery and allow for adapting treatment to the patient’s needs, he says.

(These are the best OTC pain relievers for every kind of ache.)

Pain scales in chronic conditions

Similarly, another way pain scales are used is following the progression of chronic painful conditions.

“For example, if a patient with knee arthritis sees an orthopedic surgeon, and states that their NRS is a 1-2 with activity, the surgeon may prescribe mild analgesics and rehabilitation,” Dr. Liguori says. “If the patient states that their NRS is an 8-9 at rest, more aggressive measures should be explored.”

Dr. Liguori again uses the analogy of treating a patient with high blood pressure: If after starting medication blood pressure is now normal, that dose can be maintained, but if it’s too high or too low the medication can be adjusted.

“The same applies to pain scales—if a patient is taking pain medication for a chronic pain condition with an NRS of 7, an analgesic [pain med] can be prescribed,” he says. “On the next visit, if the NRS is 0, and some side effects are occurring, the dose can be decreased. If the NRS is still 7 or 8, the dose can be increased.”

The only difference, he notes, is that pain for the most part is subjective, where blood pressure can be objectively measured. You can also discuss ways to seek natural pain relief without drugs.

The bottom line

Pain scales are a useful way for patients and health care workers to measure the level of pain they’re in, decide on appropriate treatment, and see how the treatment is working. But because they’re subjective, pain scales can’t be used in isolation, though, and will be just one of many tools in your doctor’s toolbox to understand your condition and how to improve it.

Next, here are some pain quotes to help you get through it.